A blog for Zero waste Week

Antonia Grey, Head of Policy and Public Affairs

Waste not want not.

An interesting phrase. It supposedly means that if a person never wastes things, he or she will always have what is needed.

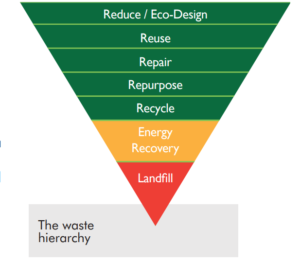

But what is waste and when does ‘it’ become ‘waste’? Following the waste hierarchy, something should only become ‘waste’ when nothing else can be done with it. In short, it can’t be repaired, reused, recycled or burnt.

Let’s consider where metal fits within this definition.

How can a constructional beam recovered from a building being demolished be regarded as ‘waste’ when it will either be reused or cut up and melted down to make new steel? It is not, and should never be, ‘waste’. Every inch can reduce the need to mine yet more primary material – iron ore. And the same goes for aluminium cans where we know that 75% of all aluminium ever produced is still in use today.

I have also been left wondering the use of the word ‘scrap’ in this industry when it is associated with recycled metal because it can mean different things to different people. For example, it is often used to describe something that is seen as worthless and no value, which is simply not the case. Metal is clearly a resource – a secondary material, a recycled material, a resource from recycling, a recycled raw material, etc. Or as one MP told me: “It is not ‘scrap’ it is reuseable steel.” It simply is not WASTE! In fact, it’s zero waste.

But it is tricky to think about change because, over the years, the word ‘scrap’ has been imbedded into the nation’s psyche. During a broadcast early in World War II, the first wartime Minister of Supply, Labour MP Herbert Morrison, implored: “I ask people to start now and save their paper, bones and scrap metal. In that way, we shall build up a great reserve of raw materials ready to be transformed into war materials.”

While the days of national campaign are no longer necessary (at least not for metal I hope, lithium-ion batteries, that’s another story!), the word ‘scrap’ is still the term recognisable to all. While when it was formed in 2001 the British Metal Recycling Association Board consciously chose not to use the term ‘scrap’ in its name, the term has continued to endure. Not least because of the affection in which it is held.

It is therefore not something which will disappear overnight, and that is right given the historical importance of the sector. However, it would be nice if term metal recycling came before the word ‘scrap’ when the sector is mentioned. This would then perhaps make it easier to start framing it as a recycled raw material or another more descriptive phrase.

Finally, I cannot look ahead to the future of steel making in the UK and the likelihood that it will use more recycled raw materials in the incoming electric arc furnaces without mentioning direct reduced iron (DRI). A lot has been said about the benefits of green and blue hydrogen-reduced DRI (HDRI), not least when it comes to decarbonisation. However, you still need iron ore to make DRI, which means there will still be mining with all the impacts on the environment that that brings. Granted it is better than the alternative, but the emissions caused by mining primary ore, even if it goes to make HDRI, must be accounted for and measured against those associated with recycled metal.